Book exposes colonial dynamics at the heart of wildlife conservation

To colonisers, Africa has been a “wild and uncontrollable environment”, home to species that can be admired (or shot) from afar.

The growing number of wildlife conservancies in northern Kenya has often raised the question of their viability regarding land rights, in a way that has pitted their establishments against residents.

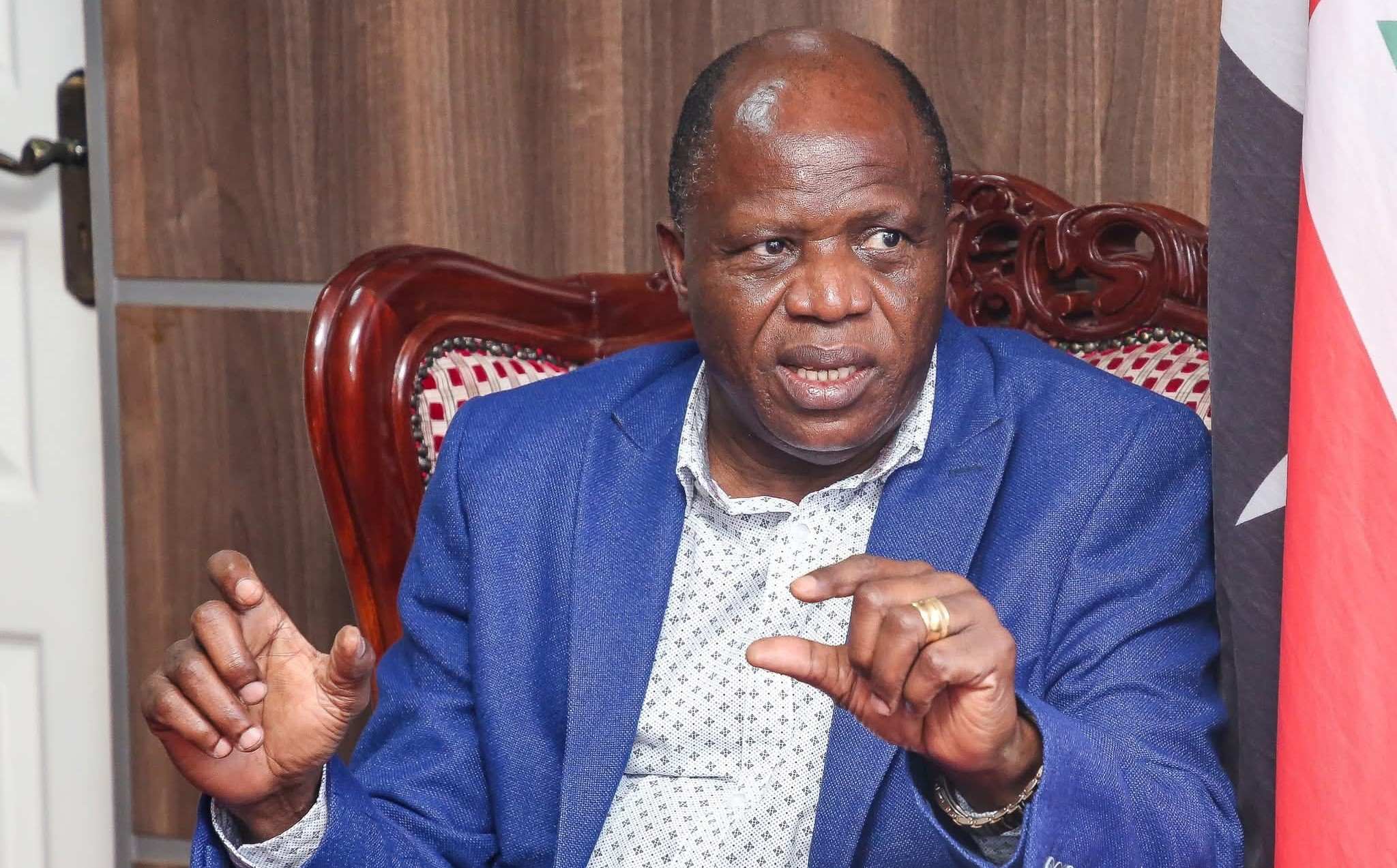

The Big Conservation Lie, a book by Dr Mordecai Ogada, a professional conservationist, sets out his concerns about the dominant conservation narrative.

More To Read

- KWS to fund operations independently amid record tourism and reforms

- Managing conflict between baboons and people: what’s worked - and what hasn’t

- Wildlife traffickers arrested in Laikipia as police seize 18kg of elephant ivory worth Sh3.6 million

- Rescue mission launched to save Masai giraffes trapped by fences in Naivasha

- Lewa, KWS launch vulture tracking project to boost raptor conservation

- Rare eastern black rhino calf born in Chyulu Hills, boosting critically endangered population

Ogada, together with John Mbaria, a Kenyan journalist, present a powerful challenge to the prevailing conservation narrative.

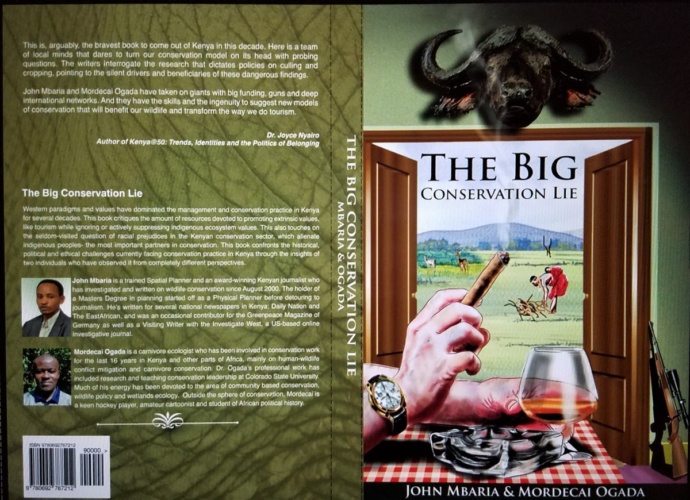

The Big Conservation Lie is written by people who are actually from one of the Big Conservation’s key target countries. It dismantles many of the environmental movement’s most troubling myths: the pristine wilderness “untouched by human hands” until European arrival; the supposed lack of interest or expertise in wildlife among native conservationists and communities; and the idea that brutal poaching would be endemic without foreign intervention, among others.

The writers sum up the essence of their argument early on: “The wildlife conservation narrative in Kenya, as well as much of Africa, is thoroughly intertwined with colonialism, virulent racism, deliberate exclusion of the natives, veiled bribery, unsurpassed deceit, a conservation cult subscribed to by huge numbers of people in the West, and severe exploitation of the same wilderness conservationists have constantly claimed they are out to preserve.”

Conventional narrative

To colonisers, Africa is and always has been a “wild and uncontrollable environment” – home to “charismatic” species that can be admired (or shot) from afar.

The cover of the book The Big Conservation Lie by Dr Mordecai Ogada and John Mbaria. (Photo: Handout)

The cover of the book The Big Conservation Lie by Dr Mordecai Ogada and John Mbaria. (Photo: Handout)

The conventional narrative has generally suggested that only European and American experts can tame or protect wildlife. The authors argue that this has given Western NGOs such as the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) enormous power.

It has also created space for white “saviours” such as George Adamson, Jane Goodall, and Iain Douglas-Hamilton to step in and be seen to make a decisive difference. There’s no place for Africans in the picture.

Ogada and Mbaria target some of conservation’s most sacred cows.

George Adamson, for example, the white British subject of the 1966 film “Born Free”, is exposed as a chancer, a failed businessman who accepted conservation donations, despite being a trophy hunter with next to no conservation expertise.

Much of the authors’ scorn is reserved for the Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS). Though it presents itself as a conservation organisation, the true face of this “service” is revealed. According to them, KWS is composed mostly of retired soldiers and mercenaries, heavily armed and organised much like a militia.

As the authors point out, the KWS receives funding, equipment, and training from Western powers, including the United States and Great Britain. This doesn’t stop it from profiting from the land it supposedly exists to protect, through tourism, and even ties to big mining and pharmaceutical companies.

In place of this neo-colonial approach, the authors advocate closer partnerships with local and tribal communities, respecting and using the extraordinary, but unacknowledged, expertise about the natural world that already exists in large parts of Kenya and the wider world.

The Big Conservation Lie is available at Nuria Book Store.

Top Stories Today